Prognostications were viewed with suspicion in

England. Prior to the early sixteenth century, those published in the country

tended to be translation of foreign prognostications, possibly because of the

dim view of prophecy taken by the Church. Pope Innocent VIII issued a Papal

Bull Summis Desiderantes Affectibus (Desiring with Supreme Emotion) in

1484, which was instrumental in the Inquisition’s suppression of witchcraft in

Europe. In 1542, Henry VIII’s Witchcraft Act defined witchcraft as a felony,

punishable by death, and removed the right of Benefit of Clergy, whereby anyone

convicted could be spared hanging if they were able to read verses from the

Bible.

|

| George Kingsley - An Ephemeris, or an Astronomical State of the Heavens - 1723 |

In such an atmosphere, it is not unsurprising that would-be

prognosticators cautiously kept their heads below the parapet; the first

printed English Almanack and Prognostication, by Andrew Boorde, acknowledged in

the preface that prognosticating was against the laws of both God and the

realm. Henry’s statute was repealed by his son, Edward VI, in 1547, and another

Witchcraft Act, of 1562, issued by Elizabeth I, was much more specific in its

definitions of what constituted witchcraft, sorcery and divination.

|

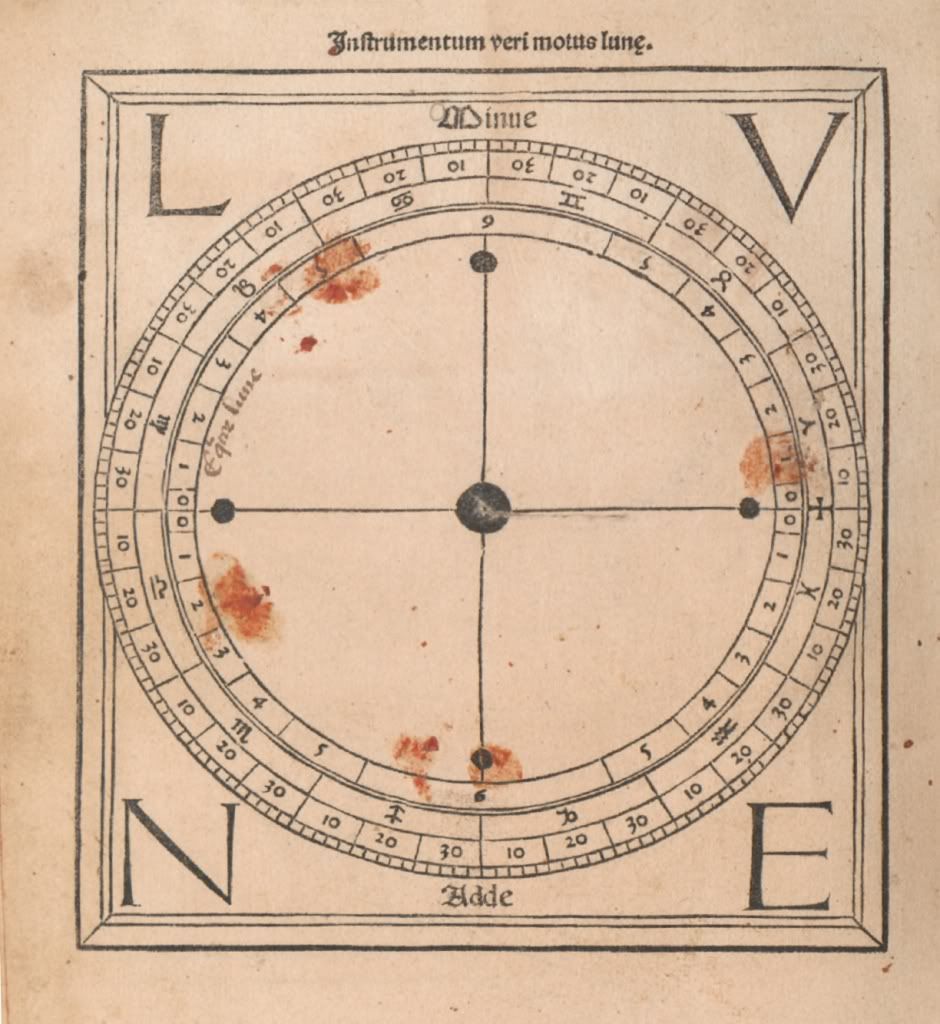

| Iohannes Regiomontanus - Astronomical Diagram for June 1483 |

English

prognosticators tended to issue quite mild prophecies, often regarding the

weather and the diseases that might follow its effects, although they did get a

little more voluble when eclipses and comets occurred, whereas their European

counterparts were much more imaginative in their forebodings of death and

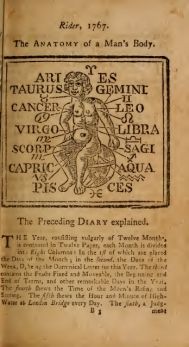

disaster. From around 1540, the separate calendar and prognostication sheets

began to be published together, annually, containing information on what

weather might be expected, the changes of the moon, eclipses, an astronomical

man with figures from the zodiac which ruled its bodily parts, the rules of

phlebotomy and so forth.

|

| Astrological Figure - Rider's Almanack - 1767 |

The former separate sheets had been intended to be

fixed on the walls of homes or merchants offices, but the later booklets were

issued to be used as cheap and readily accessible works of reference. When

Henry VIII began his reforms of the English church, the former practice of

marking the years by the Saints’ Days began to be viewed with suspicion of

popery, but the universities and the law, together with other bodies, used a

specific Saint’s day (Michaelmas, Hilary, etc) rather than the day of the

month, for marking deeds, leases, documents, term-times and so forth; following

the Reformation, the lesser Saints’ days were removed, with only the major days

noted.

|

| The Royal Kalendar - April 1765 - (Note only the more important 'Red Letter' days) |

Although published together, it was normal practice for the almanac and

the prognostication to be separated within the text, with separate title pages

(presumably so that the more puritanical patrons could discard the bits that

offended their sensibilities), and as they developed, blank diary pages were

added, together with information about the principal fairs, highways, the dates

of the monarchs and their birthdays, basic medical cures and recipes, and other

useful or interesting facts. Although the almanacs were sold for 1d or 1½d,

they were sold in such numbers that they rivalled only bibles as the most

popular and lucrative works sold by booksellers and patents were jealously

guarded.

|

| Rider's British Merlin - 1767 |

The Stationers Company required that all published books be entered at

Stationers’ Company Register, where the right to sell copies were issued

(hence, ‘copyright’), and stiff fines were liable if illegal copies were

printed or sold (12d for every unregistered copy sold was not unusual). The

Stationer’s Company rigorously protected what they regarded as their sole

preserve, and in 1603, they formed the English Stock, funded by shares from the

members, which controlled the highly lucrative trade in almanacs.

|

| Almanac Day at Stationers' Hall |

The annual

publication of the almanacs (on or about November 22nd), was marked

with immense activity at Stationers’ Hall, as porters carried out great bundles

of new almanacs to be delivered to booksellers throughout the country. They

were perfectly comfortable selling the astrological prognosticators and, from

the end of the seventeenth century, satirical works that openly mocked the

reliance of the more gullible public on the spurious prophesying. Of the former

publications, perhaps the most popular was Old Moore’s Almanack, written

by a self-educated astrologer and physician, Francis Moore, which was first

issued in 1697.

|

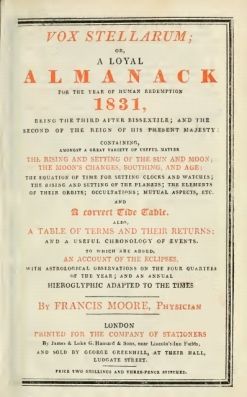

| Francis Moore - Vox Stellarum - 1831 |

His first almanac contained predictions about the weather, and

Moore went on to write the Vox Stellarum (Voice of the Stars), which

developed into his astrological Almanack, with predictions of world

events for the coming year, together with more ‘conventional’ information, and

continues to be issued today (not to be confused with Old Moore’s Almanac

– spelled without a /k/ - which is an Irish publication).

|

| Poor Robin's Almanac - 1794 |

The more

satirical almanacs began with Poor Robin’s Almanac, in 1664, which

contained such useful speculations that in January,

“… there will be much frost and cold weather in Greenland.”

Under February, the prediction was,

“We may expect some showers of rain this month, or the next, or the next after that, or else we shall have a very dry spring.”

Poor Robin’s Almanac

continued to be published until 1828, and was a coarse mixture of the

blindingly obvious with the down-right indecent, leavened with a health dose of

scepticism, although later editions replaced the bawdery with blander home-spun

homilies.

No comments:

Post a Comment